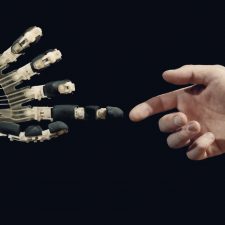

Whose Mind Is It Anyway – A curious article in The Wall Street Journal caught my attention about the ubiquitous Elon Musk, claiming that the Tesla CEO has launched a start-up company called Neuralink. Its intention is to develop technology that would allow our brains to be “wired-up” to computers.

Registered as a “medical research” firm, details are sketchy but the report suggested that Neuralink plans to develop what it calls “neural lace” technology, which would implant tiny electrodes into the brain, allowing for improved memory and providing humans with enhanced AI capabilities.

Apparently, the company is already busy trying to sign up leading academics in the field, with many believing the time is fast approaching when humans may be able to upload and download thoughts.

It seems that science fact has now superseded science fiction.

But what are the implications of this kind of technology and where could it bring the most benefit and more importantly, the most harm?

With this in mind let’s take a theoretical trip into this world of tomorrow to get a sense of the opportunities it could offer as well as the challenges we might have to face.

The idea of being able to hook the brain directly into a “thought repository” somewhere in the cloud entertains endless possibilities but also fills me with a certain feeling of dread.

The benefits are immediately obvious – everything from education, travel and communication to medical and mental health could all gain significantly.

Imagine being able to learn and absorb data directly into the brain. Think about how the journey from A-B could be simplified with a fully internal sat-nav system that didn’t need a screen. In essence, technologies like Amazon’s Alexa and Google Home are already leading the way, helping us to work in a new form, without the need for visual aids.

Even from a practical viewpoint, the ability to access thoughts, images or even complete conversations in the same way you would currently reach for a book in a library could elevate our mental capabilities to new levels.

Consider the advantages of being able to think of something and immediately have access to it via a link out to the web or possessing the ability to call someone directly with your mind?

You want to turn the heating on before you get home or order a meal to arrive at the door just as you do, simply initiate the mental instruction and it can be a reality. It’s just a process. Rather than my brain telling my finger to hit a series of buttons on my smartphone to initiate a command, I can just think it.

As we age the ability to archive our memories and thoughts into a personal, interactive and evolving diary of our lives could help us revisit experiences from our past in a completely new and exciting way. Sharing those memories with our loved ones could become a more engaging and intimate exchange that transcends anything we currently comprehend.

It’s coming, there’s no question about it and – to paraphrase a quote from Star Trek – resistance will be futile.

In reality, we’re already halfway there with mobile phone technology.

When someone asks you a question you don’t have the answer to you’re only ever a Google search away from the solution. Now take that process a stage further and remove the physical device completely, replacing it with a direct link to the brain and you have the ultimate, intimately connected search engine.

A positive tomorrow then but there are also reasons to be concerned about this technology. Anyone who has ever had a computer or social media account hacked will know the debilitating effect this can have on your life.

Imagine then, if you can, what opportunities for the criminal elite a direct link through to our brains could facilitate. A process that allows for two-way communication is always going to be at risk of unwarranted or illegal entry. It’s simply the digital equivalent of an open front door, unlocked car or unattended bag.

Then there is the question of who benefits most from this new connected society.

The optimist in me will extol the virtues of a new era of communication but the sceptic is likely to point a finger at government and corporations, both of whom would see significant opportunities to potentially control people in an entirely new way.

There is also the direct effect the digital revolution around us is having on our physical health. Surely it is more than a coincidence that global obesity levels are at their highest, especially amongst young people, running in parallel some would argue with our adoption of technology.

Think about how we use our brains today and for those of us who are true “digital immigrants” then go back 30 years and consider how that process has changed.

It is a story I tell many times to my son and my nephews but it remains a building block for this argument.

I was around as an adult before the dawn of the mobile phone as a mass-market product. I remember what it was like to have to write numbers down and often commit them to memory. Since then, first-generation mobile devices and after them, smartphones infiltrated my life. The people and places I knew have changed and their numbers have changed with them.

Today, the only number I can still recall from memory is my father’s house phone, simply because he never changed it throughout that entire period of digital evolution. The convenience of technology means I don’t need to remember these details any more.

And this is often the case put forward by most futurologists and supporters of technological change – technology has taken away the burden and increased our leisure time.

But what are we doing with that leisure time?

The cynic in me would suggest we are simply handing over more of our independence to technology. And that means corporations. We are becoming lazy, plugging ourselves into a system that only wants to understand us so it can exploit us.

And what happens if there is a system failure, once we have committed everything we are to the new connected world order? We all know the current sense of frustration when we cannot connect to our social media platforms or the Internet. If we have uploaded all the details that make us who we are to the cloud, then without that active connection will we just be sitting around like empty vessels waiting for our memory banks to reconnect again?

I guess the ultimate question we need to ask ourselves is how far do we as a society want to buy into this connected vision. It has a place but it needs to be closely monitored. We know so little about the human mind in relative terms so invading it with technology before we fully understand it could bring about challenges we haven’t even contemplated.

Returning to my point about digital abuse, is it so far-fetched to believe that the more unscrupulous out there might look to manipulate those thoughts uploaded to a cloud “memory bank”? Could it be possible – in the same way that our physical devices can be hacked and altered – that the very fabric of these unique thought processes could also be manipulated?

Do I want my inner thinking bombarded by intrusive advertising or worse still, subliminal messaging from organisations trying to sell me stuff in a completely new way? Will I need to be connected when I sleep and if so, can how I dream and what I dream be affected? Will I wake to crave a soft drink that has been marketed to me in my downtime or feel the urge to buy a new brand of trainers when I head off to the shopping mall?

It would leave us with the ultimate dilemma of not being able to trust our own thoughts and begs the question proposed at the very start of this article.

Then, whose mind would it really be?

B W

Tags: Connectivity, Future Technologies

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It